The Invisible Fugue: The Poetry and Metaphysics of Ellen Hinsey

- Luke Fischer

- Sep 28, 2025

- 17 min read

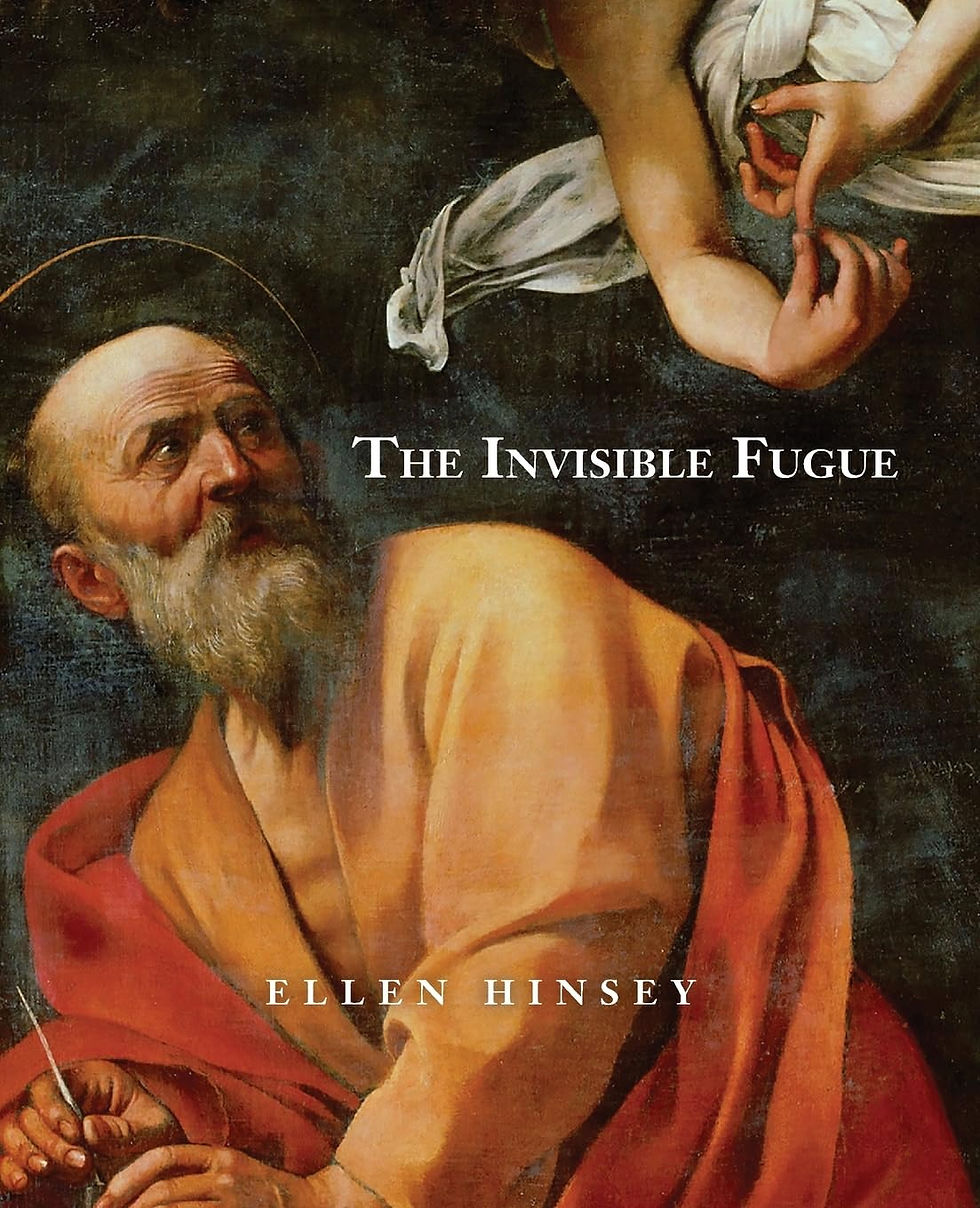

Luke Fischer on Ellen Hinsey's The Invisible Fugue

Two souls, alas, reside within my breast, and each is eager for a separation: in throes of coarse desire, one grips the earth with all its senses; the other struggles from the dust to rise to high ancestral spheres.

- Goethe, Faust I

Ellen Hinsey is one of the most accomplished US-born poets writing today, and she came to prominence early in her career when her collection of poems, Cities of Memory (1996), won the Yale Series for Younger Poets prize. The author of nine books of poetry, essays, dialogues and literary translations, Hinsey’s distinctive philosophical, historical and political orientation, along with the rare gravitas of her poetry, make her work stand in relief from the writings of her celebrated North-American contemporaries.

Based in Paris since 1987, Hinsey has travelled extensively in Central and Eastern Europe, and she has written both scholarly and poetic works on the poetry, politics, and history of this part of the world. In its philosophical tenor as well as in its concern with history and political injustice, Hinsey’s poetry furthers, in her native tongue of English, the diverse tradition of major Central and Eastern European poets, which includes Osip Mandelstam, Paul Celan, Anna Akhmatova, Joseph Brodsky, Czesław Miłosz, Wisława Szymborska, Adam Zagajewski and Tomas Venclova. In the introduction to her book-length conversation with Venclova, Magnetic North, Hinsey quotes a statement by Miłosz, which she explains could have just as easily been written by Venclova. In turn, this statement rings true of Hinsey’s own poetry: “we [poets of this region of Europe] tend to view it [poetry] as a witness and participant in one of mankind’s major transformations.”

I first encountered Ellen Hinsey’s poetry in 2015 when she gave a reading at the International Literature Festival in Berlin. Two profound qualities of Hinsey’s poetry that stood out and which I have come to know more intimately in my close reading of her work are: 1) her astute moral witness to political and humanitarian atrocities and 2) what I would like to call the imaginal or spiritual dimension of a number of her images.

The first of these two qualities is foregrounded in her collections Update on the Descent (2009) and the sequel of sorts The Illegal Age (2018), while the second is foregrounded in her new book-length poem The Invisible Fugue, as well as in her earlier collection The White Fire of Time (2002/2003). The way her poetry embodies the first quality, the astuteness of her moral witness, markedly differs from much political poetry today, which often wears its ideology on its sleeve and shows too little distinction from what might be shouted from a megaphone at a demonstration for an activist cause. While its message may be generally commendable, progressive even, it tends to forget that what is distinctive about poetry as an art form is how its content is conveyed and the inseparability of poetic content from its individuated aesthetic form. If the form is no more than the means of communicating a general, abstract message, then a poem lacks what is distinctive about a work of art.

Poets, like Hinsey, negotiate between two poles in order to produce significant poetry; these are timeliness and timelessness. In the contemporary milieu few poets are drawn to the contemplation of timeless or perennial themes. Rather, the other extreme is widespread, namely a conspicuous topicality. However, a topicality or timeliness that does not draw sustenance from perennial human concerns gives it a “best before” date, which is contrary to one of the central impulses behind art: to create works of lasting significance. In contrast, great poetry often combines a deep awareness of its author’s present time with an orientation towards universal human concerns. It is precisely these two qualities that are united in Hinsey’s poetry, which speaks to our time, but is not of our time. As Zagajewski tersely put it in an endorsement of an earlier collection of poetry by Hinsey: “[it] is a stunning quest for essential things, a pursuit that goes courageously against the current of contemporary American poetry.” Hinsey’s poetry has a pitch-perfect conscience. One feels that every word has been carefully weighed according to not only its aesthetic but also its ethical resonance before it is committed to the page. Her poetry bears witness to violence and atrocities, intimates the disastrous future trajectories of current tendencies and events (in this Hinsey’s poetry has a prophetic dimension), while always being attuned to universal human ideals. In these qualities and in her seriousness, Hinsey bears an affinity with the philosophy and ethics of Simone Weil (a thinker she admires), without being as severe as Weil, who quite possibly starved herself to death in her solidarity with those deprived of adequate food during the Second World War.

The second quality, the imaginal or spiritual dimension of many of her images, finds its deepest articulation to date in The Invisible Fugue. This masterful book-length poem is preceded by several epigraphs, which serve to frame some of its central concerns.

Hinsey’s Epigraphs and Why They Matter

The opening epigraph from Celan––“Illegible this world”––stands for one pole in the tensions that constitute the problem poetically addressed by Hinsey’s book. The horrors and atrocities of human existence, which Holocaust survivor Celan knew well, confront us with a world that seems inherently unintelligible, meaningless, exiled from the Good, in short, illegible. The title of Hinsey’s book also brings to mind Celan’s most well-known poem “Death Fugue” (Todesfuge), although as a kind of photographic negative, for Hinsey’s explicit references to the transcendent music of Beethoven hold a more central place in The Invisible Fugue.

The third epigraph (I will come back to the second) is taken from the consummate German poet of the romantic era Friedrich Hölderlin, a poet with whom Celan identified as a fellow outsider from an earlier period. Celan ended up taking his own life, and Hölderlin lost his mind and spent the entire second period of his life in a deranged state. Hölderlin is a poet, who intimately knew the heights of the human spirit and the darkness of despair. In the first respect he represents the opposite view to the world being “illegible.” In his poetic raptures and mythopoetic reflections both nature and history are disclosed as meaningful processes in which the poet can intuit the Divine or the Absolute––the ultimate unity of being. In short, the world is legible to the inspired poet. The divine unity of being is often poetically figured by Hölderlin as a “Father-God” in one guise or another. In the epigraph chosen by Hinsey (and elsewhere) he is represented as the “Thunderer,” alluding to the Greco-Roman figure of Zeus/Jupiter: “It’s then I often hear the thunderer’s voice / At noon, when he brazenly comes near.” This dramatic embodiment of the Absolute is already suggestive of the music of Hölderlin’s contemporary, with whom he shared the same birth year (1770), Beethoven. Moreover, while in the late 1790s Hölderlin regarded elevated experiences of the beauty of nature and art as the privileged sites in which we glimpse the divine unity of existence, he more and more came to discern this unity even in the midst of extreme opposition, such as the relationship between the tragic hero and his fate in ancient Greek drama (which he described as “the metaphor of an intellectual intuition” of the Absolute). It was, however, Hölderlin’s great misfortune that his own biography was a tragedy without catharsis.

The second, unusual epigraph is the score of the opening bars of Beethoven’s Great Fugue (Große Fuge in B-flat Major, Opus 133), a work that was originally composed by Beethoven as the final movement of his String Quartet No. 13 (Opus 130), but was regarded by his contemporaries as unintelligible. For this reason, Beethoven was asked by his publisher to compose a new final movement for the String Quartet, and the Große Fuge was thus bequeathed to posterity as an independent work. While it is still regarded as one of Beethoven’s most challenging pieces, it is also perceived as one of his greatest compositions (Stravinsky described it as "an absolutely contemporary piece of music that will be contemporary forever"). Hinsey’s choice of this Beethoven “epigraph” as well as a number of quotations from Beethoven’s diaries that are used as epigraphs to each part of the book (as well as one other “musical epigraph”) is far from arbitrary.

Few, if any, composers have known and expressed the heights and depths, the ecstasies and despairs of the human spirit to the extent of Beethoven. In Beethoven the polarities of dark and light are articulated in their extremes, while nonetheless not becoming so opposed to one another that they suggest an irresolvable Manichaean battle between good and evil. In contrast to Hölderlin who could not hold together the duality of divine inspiration and existential turmoil, Beethoven’s music and biography represent a triumph of the human spirit, which affirms the entirety of being and gives meaning to the drama of human existence. Beethoven was virtually deaf by the time he composed the Große Fuge, yet even this personal disability could not stand in his way as a composer, but is rather overcome in a manner that has its philosophical equivalent in the dialectical strife and speculative progression of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit in its final arrival at Absolute Knowledge.

Hinsey’s book is unusually formatted such that the lines of the seven-part poem are set at the bottom of each page, with much white space remaining above. This can be viewed as an invitation to the reader to think of Beethoven’s Große Fuge as continuing to play in the white silence of the page, as though secretly accompanying the unfolding poem. (The blank space is also suggestive of the invisibility and ineffability of the Absolute.) More specifically, six of the seven parts of Hinsey’s poem are named after indications from different sections of Beethoven’s score, the first being Overtura. Allegro (the seventh part is similarly named after the fifth movement of String Quartet, Opus 130). Yet, we must heed that Hinsey’s book is not titled The Great Fugue but rather The Invisible Fugue and also give some thought to the form of a fugue.

A fugue, among other things, is characterized by the way in which one instrument takes up a motif from another and develops this motif further. There is thus a continuum, variation and process of transformation in the way in which each instrument relates to the other. A greater harmony or unity is expressed through the differentiations and, in both Beethoven and Hinsey, this includes the heights of divine inspiration and the abysses of fallenness and despair. Hinsey’s book is at once a philosophical, metaphysical and cosmological poem that succeeds in affirming the ultimate goodness of being, in spite of the extreme oppositions we experience between light and dark, good and evil, legibility and illegibility, and perhaps most centrally, eternity and time. The unity that is divinable in the vicissitudes of human existence and in spite of all the atrocities in the world is generally invisible or unapparent, and herein lies the meaning of “Invisible” in the book’s title. Resonating with Hölderlin’s view of the vocation of the poet, the task of poetry is to make the world legible, to mediate a sense for and affirmation of the unity of being. The fugue of existence is invisible and difficult to discern through the veil of dailiness as we are so often overwhelmed by the extreme oppositions we see in the world, the prevalence of violence, the emotions of senselessness and futility.

On the Structure and Significance of The Invisible Fugue

Hinsey’s other recent books have concentrated on affirming the place of poetic conscience as the individuated instantiation of the good, which bears astute witness to violence and suffering as a spiritual act of resistance and compassion, while The Invisible Fugue is a more positive poetic statement of the ultimate metaphysical good. Its central concern is the relationship between eternity and time, the one and the many, and unity and difference, which are integrated in a fugue-like development and complexity. As the poet Jakob Ziguras has suggested, the poem is marked by an “authority and authenticity” that could be interpreted as a testimony to the rare event, in the context of secular modernity, of a night of Pascalian fire or encounter with the Divine. The Invisible Fugue is also a nature poem, but one that renews and updates the elevated concerns of the nature poetry of the romantic era. For as much as the portrayal of the natural and rural environment presents a symbolic landscape of the conditions of human finitude, it also depicts them in their concrete particularity and as mediators of insight into the spiritual realm.

The opening line of the book-length poem alludes back to the epigraph from Hölderlin and the sky as the locus of divine manifestation: “Tonight, under this thunderous sky.” The speaker is depicted as standing in a “damp field” in “midnight’s last hour,” where she bears witness to the firmament as a manifestation of the Divine, which is addressed in the second person “You” (Hinsey never uses the word “God” but rather explores other names for what exceeds all names). The allusions here include those of the planetary spheres such as they were understood in the late Middle Ages and indelibly poetized in Dante’s Divine Comedy, but also go back much further. In recollection of Heraclitus, the pre-Socratic philosopher of cosmic fire and the Logos, the firmament is depicted as the realm in which “Your great fire still surges.” In addition, Hinsey invokes the Pythagorean “music of the spheres”:

It would be a mistake to read these lines as if they were merely intending to allude to ancient conceptions of the heavenly realm out of a scholarly interest in intellectual history. Rather, Hinsey’s lines convey the immediacy of a poetic vision of the night sky, in which the stars and planets are experienced as mediators of insight into the spiritual realm, and even of the ultimate ground and source of being––the “First principles / surpassing understanding.” In the elevated romantic meaning of the term, this is an imaginal vision of the heavens, the sky apprehended as a symbol of the eternal through the organ of imagination (as Coleridge theorized it). The speaker strives to divine the heavens as the moving image of eternity (Plato), but at the same time feels the pull of gravity, feels how human existence is mired in the contingencies and darkness of the temporal order. The speaker strives to hold on to the paradisiacal vision, but is “Embroiled in our world of shadow intent,” while “the heart persists in waywardness and loss.” The speaker––and by extension humanity––is caught within the tension of light and dark, heaven and earth, the eternal and time, divinity and mortality. In its philosophical and mystical tenor and its meditations on the relation between the timeless and time, Hinsey’s poem bears comparison to Eliot’s treatments of this theme in Four Quartets. At a formal level, this theme is reflected in the long sentences––the first full stop comes at the end of the first part––that suggest a fugal continuity and a paradoxical suspension of time within the temporal unfolding of the poem––the reciprocal entwinement of the timeless and time. This stylistic quality––long sentences with many clauses––is something Hinsey already used to masterful effect in her previous books.

Part II of Hinsey’s book deals with our fall from the Divine into the “temporal world” of “complexity,” contingency and imperfection, in which we hazard our way according to “fragmentary instincts.” This is contrasted with the heavenly vision of the first part, which is now described as the “First Grammar” and “First vowels and First tense // Of which we are always, and ever, mere fragment.” The vision of divine plenitude thus comes into tension with our fallen and fragmented grasp of the unity of being, our lack of orientation and “metaphysical exile” (as E. M. Cioran describes the human condition, though Cioran differs from Hinsey in regarding this exile as inexorable). Importantly, the opening vision of the universe is now rendered as one of Language––the cosmos as Logos––as the divine script that is legible to the divining poetic mind. Hinsey does not specify a conception of the Logos that is restricted to a particular religious confession and thus it is left to the reader whether to interpret this as the Logos of Heraclitus, the Word of Christianity, or creation as spoken by the God of Genesis shared by Judaism and Christianity.

In spite of our cosmic exile, our fallenness in time and shadow, we are nevertheless able to glimpse the presence of the Logos in the language of the natural world: “The elliptical language of hoarfrost” and “The gale’s litany in weeds.” This calls to mind, for me, the opening of the wonderful unfinished novella The Novices of Sais by Hölderlin’s contemporary Novalis, which invokes “the language of nature” (in a sense that is influenced by Jacob Böhme): “that great cipher which we discern everywhere, in wings, eggshells, clouds and snow.” Hinsey also echoes Hopkins’s notions of “inscape” and “instress,” in construing these signs of nature as “in-patterns of the cosmos’ intent.” But so often the world is illegible to us; we find ourselves lost in the confusion of the “mind’s impenetrable thicket” only able to long for a transcendence of this condition: “Filled only with vague hope and unreliable will–– / And the desire to be stilled.” We find ourselves in cosmic solitude, unable to lift our vision towards the splendor of the transcendent.

Part III of The Invisible Fugue describes our lonely wanderings during the day (in our loss of the midnight vision) in which we seek a sign and trace of the “beloved” –– the spiritual background of the natural environment and the telos of our longing. In our uncertain wanderings we also pass by a city that is “approaching ruin,” a symbol of present-day civilization. This part of Hinsey’s book is animated by the question as to how, in our fallenness, we can become receptive to an encounter with the spiritual, as well as to how, through the encounter with the other, we can reconcile ourselves to our earthly time.

In Part IV, the longing for union with the divine is redirected towards the erotic and carnal union with a beloved, thus deepening the poem’s reflections on how human existence is entangled in the realm of time, embodiment and desire. As the fugal sequence moves through the passage of time from night into day, which is at once descriptive and symbolic, we find ourselves now at midday in the burning heat of summer. The longing for an encounter with the “beloved” other finds a different kind of fulfillment in the carnal union of love-making. Hinsey portrays this bodily entanglement of lovers both vividly and, as always, in deftly crafted language. Here passion and desire find their fulfillment and a genuine, though transient, union is achieved. At the erotic climax “Day’s captivity” –– the prison of this world –– is released, “making one / Of our separateness, in embrace.” But after this erotic union, an intensified feeling of isolation emerges, we find ourselves again in cosmic exile.

Moreover, there is a stark contrast between the Heraclitean fire invoked in Part I and the eros of “desire’s rage––and fire,” with which Part IV concludes. This fire of passion recalls an epigraph to Part IV that Hinsey took from her notebooks, “To join with rage, / The fire of time––” (a formulation that resembles the title of her earlier poetry collection, The White Fire of Time). Hinsey’s contrast of heavenly fire (what Hölderlin called “the fire of the heavens”) with the carnal fire of time and desire also recalls the two fires of Eliot’s Four Quartets (“To be redeemed from fire by fire”). Yet, the locus classicus that is more relevant to Hinsey’s framing of the heavenly realm and the carnal “beloved” other is, of course, Plato’s Symposium, where the erotic desire for bodily beauty is seen as a step on the way towards a higher fulfillment of eros in the spiritual contemplation of divine beauty and wisdom. There is no rejection of physical desire in Hinsey’s poem (she speaks of “love’s holy alphabet”); yet, at the same time, in a Platonic sense, it is seen as an imperfect realization of the eros that finds its higher telos in a spiritual beholding of the divine.

Set amidst a symbolic landscape, Part V elaborates on the theme of the onward rush of time, the horizontal, uncertain flux that shows little evidence of transcendence. Through the changing weather––including hailstorms and tempests––the cycles of life and the seasons (“gestation, maturity, decay”) as well as through our own physical ageing, our emotions of grief and loss, we find “no respite” from “the supremacy of the Emperor hours.” Hinsey’s vision of the human condition is one in which we are often estranged from the deeper meaning of existence; we are, nonetheless, offered glimpses of a meaningfulness that is greater than the finite version of ourselves. The world, nature and history often seem illegible, but we can aspire to deepen our comprehension and begin to decipher them. In this tension between the infinite and the finite, the spiritual and the carnal, the vertical and the horizontal, the eternal and the temporal, we find ourselves “torn between animal––and // Illumination––.”

After approaching a feeling of being inevitably condemned to the horizontality of time and existence, a prison-house of immanence devoid of transcendence, Hinsey returns us, in Part VI, to “Intimations of that higher realm” that arise “in the innocent silence of the fields.” With a knowledge of Hinsey’s other books, which deal profoundly with the subject of human violence, the adjective “innocent” stands out. “Innocent” fields concomitantly summons its antonymic expression, which we might render as “killing fields.” Hinsey’s “intimations of that higher realm” are not of a morally neutral divinity but rather of the Good, which can only be apprehended when we are attuned to a primordial innocence within ourselves (“the good” that “seeks the Good”), when, to quote Baudelaire, we are kindred with “the race of Abel.” As in the book’s beginning, the Divine is once again addressed as “You” and the poem reaches its climax in the elaboration of a vision in which the oppositions of dark and light, the eternal and time, are reconciled in a deeper unity:

The “indivisible landscape” can be regarded as synonymous with the “invisible fugue” of the book’s title. In spite of all the oppositions of existence, the poet’s vision here divines a unity that underlies all––the “Understructure that eludes interpretation,” but which the poet nonetheless “follow[s].” The poet’s “tongue” is now “full of … Testimony / / Of Your illustrious trace.” This is Hölderlinian in its sense of the poet’s vocation as one of mediating a relationship with the Divine and, more specifically, in its implication that such a vision is the source of inspiration for Hinsey’s poem The Invisible Fugue.

The “indivisible landscape” is the unity and meaningfulness that Hölderlin discerned even in the oppositions of Greek tragedy. It is also the meaning that Beethoven gives to grief and despair, in that by passing through their purging fire, we become more mature and wiser. It is important to mention that the “invisible fugue” is also the divine spring from which new and vital impulses can enter into the world––the “spring of all that inwardly … Pulses.” Hinsey’s Divinity is in no sense tame or placid, but rather the “Wind that violently thrashes / The fragile spring staves,” a formulation that at once carries a pneumatological resonance and is suggestive of the intensity of Beethoven’s music. Finally, at the apex of this sequence we also hear echoes of the final verses of the mystical Maitri Upanishad, with its evocation of the ungraspable and multi-faceted nature of the divine.

Part VII––the poem’s solemn, final part––elaborates this vision but in a more quiet and reflective tone. This resonates to some extent with its “epigraph” from the opening bars of the “Cavatina,” the fifth movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet, Opus 130, which in Beethoven’s original composition was immediately followed by the Große Fugue. The poet’s vision of divine unity grants her the strength and fortitude to “praise” existence in spite of the inevitability of mortality and all that is fallen in the world:

If all this is true, the poet ponders, then the unity of being has always been invisibly present, even when we feel ourselves to be lost without purpose in cosmic exile:

Here the polarity and seeming opposition between the eternal and time, the vertical and the horizontal are mysteriously unified, while nonetheless maintaining their tension with one another.

The Invisible Fugue is the positive counterpart to the darkness of history and the contemporary world that has formed the focus of Hinsey’s other recent books. If those books bear witness to human violence in the light of a morally uncompromising conscience and warn us of the potentially catastrophic trajectories of widespread tendencies of current civilization, The Invisible Fugue thematizes the divine sources from which we must draw sustenance if our civilization is to be rejuvenated. The place of the natural environment in The Invisible Fugue bears an affinity with Miłosz’ book-length poem Treatise on Poetry, which, in its dialogue with nature––against the backdrop of the horrors of history––looks for sources of renewal for poetry and society.

In these difficult times when many people opt for the escapism provided by the passive consumption of entertainment instead of actively engaging with serious art, Hinsey’s work attests to the power of the marginalized art form of poetry to awaken our conscience and ignite the creative spark of existence.

Luke Fischer is a poet and philosopher. His books include his third collection of poetry A Gamble for my Daughter(Vagabond Press, 2022) and the monographs Philosophical Fragments as the Poetry of Thinking: Romanticism and the Living Present (Bloomsbury, 2024) and The Poet as Phenomenologist: Rilke and the “New Poems” (Bloomsbury, 2015). His co-edited volumes include The Seasons: Philosophical, Literary, and Environmental Perspectives (SUNY Press, 2021) and Rilke’s “Sonnets to Orpheus”: Philosophical and Critical Perspectives (Oxford University Press, 2019). He holds a PhD from the University of Sydney where he is also an Honorary Associate in Philosophy. For more information, visit: www.lukefischer.net